|

Takashi Murakami

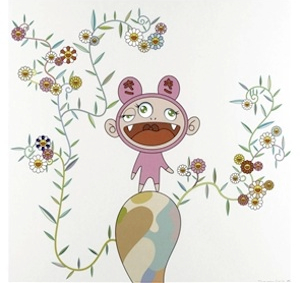

Kiki With Moss

2004

Lithograph

27 x 27 in.

Edition of 300

Signed and numbered in ink

About This Work:

Son of a taxi driver and a housewife, Murakami grew up in Tokyo, then attended Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music, the country’s most prestigious arts institution. He holds a Ph.D. in Nihonga – the refined hybrid of European and traditional Japanese painting that was invented in the late 19th century. Nihonga paintings are employed to render likenesses of bouquets and landscapes, in accordance to traditional Japanese artistic conventions, techniques and materials, to suit the influx of European tourism and an export market to the West.

Prior to 1868, Japan’s Meiji period, the word for “fine art” did not exist in the Japanese language. It was only after this time that the country imported this foreign ”art” notion and created a vocabulary for it. The blurring of high and low, of West and East, remains characteristic of Japanese society.

Takashi Murakami is the one that, better than any other Japanese artists, has been able to incorporate all the cultural contradictions and influences of Japan that even today permeate the Japanese society. He is one of the most well-known Japanese contemporary artists.

Murakami aligns himself with the geeky, obsessive fans and collectors of the Japanese manga, anime and animations, whose name is ‘otaku’. By combing Nihonga painting with otaku aesthetic, merging tradition with contemporary, he has literally changed the face of Japanese art. Some years ago Murakami elaborated a theory under the clever rubric ”Superflat”, linking the flat picture planes of traditional Japanese paintings to the lack of any distinction between high and low in Japanese culture. On stylistic grounds he grouped together some traditional artists of the Edo period (1603-1868) with the creators of modern-day animated films, arguing that there were important formal similarities in the flatness of their work. Now, having analyzed Japanese pop culture aesthetically, he is turning his scrutiny to the function that superflatness might be serving in contemporary Japanese society. Superflat can be described as a flattening process that conveniently released both the artist and the viewer from grappling with the contradictions of Japan’s wartime experience as predator and victim and postwar status as economic rival of, and political subordinate to, the United States.

Murakami maintains that respectable Japanese artists largely ignored the horrors of World War II and the humiliations of the postwar occupation, relinquishing the subjects to the ‘otaku’, who transported these tough realities into the realm of cartoon fantasy. In many of the classic manga and anime stories the plot revolves around a bomb or radiation device that devastates Tokyo. ”I thought: why does otaku culture so many times have an explosion that looks like an atomic bomb? I was trying to find out why otaku people are always repeating the same scene and why I was so interested in it myself“. He concluded that otaku raised ”a mirror” to a reality that the larger culture preferred to ignore. In childlike animated forms, anguished truths were stripped of their historical context.

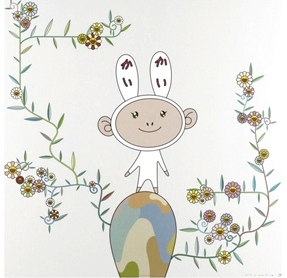

This week’s Work Of The Week, KiKi With Moss, is from a two parts suite consisting of Kiki and his counter partner KaiKai. KaiKai and KiKi loosely translate into good and evil or the Angel and Devil. These characters have come to be seen as avatars of the opposing aspects of Murakami’s own character and they can be interpreted to be his ultimate self-portrait.

KiKi With Moss and KaiKai With Moss, 2004

Murakami’s work embodies some interests that extend far beyond Japan. It’s a blend of fantasy, apocalypse and innocence. He speaks about important themes such as the atomic bomb, the war, the issues that are affecting Japanese culture and society past and present, the relationship between the Western world and Japanese culture – and he does it through colorful, cartoon-like characters that at times have smiling faces and mesmerizing flowers, and at times have disturbing jagged teeth like fangs, making the cute violent. It’s all the disparate elements combined that speak to the moment and reveal a deeper meaning to a culture that Murakami sees as divided, confused, confident and progressive. A culture full of hope for the future, but one that needs to remember and embrace its past.

|