Tag Archives: workoftheweek

WOW – Work Of the Week – Alexander Calder “Our Unfinished Revolution” Portfolio

WOW – Work Of the Week – Robert Indiana “American Dream #5”

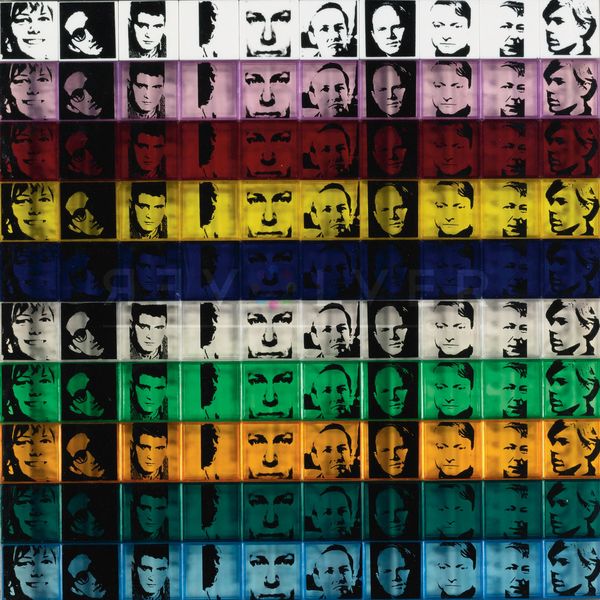

WOW – Work Of the Week – Andy Warhol “Portraits Of The Artists”

WOW! – Work Of the Week – Claes Oldenburg “Typewriter Eraser”

WOW! – Work Of the Week – Keith Haring “Free South Africa #2”

Untitled (Free South Africa #2)

1985

Lithograph

32 x 40 in.

Edition of 60

Signed, dated and numbered in pencil

__

ABOUT THIS WORK:

Though many associate the artist Keith Haring with his seemingly innocuous images of barking dogs, crawling babies, beating hearts and flying saucers, his work often tackled social justice issues – from nuclear proliferation, to AIDS, to the environment to racial and income inequality. He was very political and engaged in many of the relevant questions and issues of his time and talked about heavy themes such as racism and apartheid, which Haring tirelessly rallied against— notably printing and distributing 20,000 “Free South Africa” posters in Central Park in 1985.

This work, titled Free South Africa #2, is part of a trilogy which shows us the relationship between black and white people (actually black majority and white minority) in South Africa, during years of repression and inequality, when racial segregation was the rule: it was called “apartheid” (literally “separation”). The black figure in this picture is bigger than the white one, symbolizing the great disparity between the black majority and a few white people that had the power to rule the country during those years. To convey the inequality of the white minority’s powerful grasp on the black majority, the white figure has tied a rope around the black man’s neck. To show hope and signs of defeat, Haring depicts the gigantic black figure, crushing or stomping out this inequality, marked by a red X.

The figures are placed within the rectangle with Haring’s typical balance and sense of the space, the relationship between the busy and the empty space in the image is tempered, despite of the too different sizes of the figures. The lines stemming from the figures inform us of the movement and the rage of the black man and the worry and inevitable destiny of the white figure, who is about to be crushed.

Using the words of Julia Gruen, a friend of Haring’s and executive director of the Keith Haring Foundation, “…we can feel that image really in the simplest possible way spoke to a kind of political activism. . . It’s really about fighting against oppression. It’s about bucking the system. It’s about questioning authority”.

Haring’s genius was his ability to communicate very directly, very immediately through his chosen symbols and iconography, he could reduce a work to the fewest forms possible to make his point, and racism was an issue that was of paramount concern to Haring. Activism was at the heart of his artistic practice. This is something that is often forgotten or overlooked because the typical whimsical images that have saturated pop culture, and are the ones that are easiest for the masses to consume. However, the joyfulness and a wonderful lightheartedness in his work, is a message of his vision and strong hope of a better world to come.

ABOUT THE ARTIST:

Keith Haring found a thriving alternative art community that was developing outside the gallery and museum system, in the downtown streets, the subways and spaces in clubs and former dance halls. Here he became friends with fellow artists Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as the musicians, performance artists and graffiti writers that comprised the burgeoning art community. Haring was swept up in the energy and spirit of this scene and began to organize and participate in exhibitions and performances at Club 57 and other alternative venues.

Haring was able to push his own youthful impulses toward a singular kind of graphic expression based on the primacy of the line.

In 1980, Haring found a highly effective medium that allowed him to communicate with the wider audience he desired, when he noticed the unused advertising panels covered with matte black paper in a subway station. He began to create drawings in white chalk upon these blank paper panels throughout the subway system. Between 1980 and 1985, Haring produced hundreds of these public drawings in rapid rhythmic lines, sometimes creating as many as forty “subway drawings” in one day. This seamless flow of images became familiar to New York commuters, who often would stop to engage the artist when they encountered him at work. The subway became, as Haring said, a “laboratory” for working out his ideas and experimenting with his simple lines.

Between 1980 and 1986, Haring achieved international recognition and participated in numerous group and solo exhibitions. His first solo exhibition in New York, held at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in 1982, was immensely popular and received critical acclaim. During this period, he participated in highly renowned international survey exhibitions such as Documenta 7 in Kassel Germany, the São Paulo Biennial and the Whitney Biennial. Haring completed numerous public projects in the first half of the 80’s.

Throughout his career, Haring devoted much of his time to public works, which often carried social messages. He produced more than 50 public artworks between 1982 and 1989, in dozens of cities around the world, many of which were created for charities, hospitals, children’s day care centers and orphanages

Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. Haring enlisted his imagery during the last years of his life to speak about his own illness and generate activism and awareness about AIDS.

During a brief but intense career that spanned the 1980s, Haring’s work was featured in over 100 solo and group exhibitions. By expressing universal concepts of birth, death, love, sex and war, using a primacy of line and directness of message, Haring was able to attract a wide audience and assure the accessibility and staying power of his imagery, which has become a universally recognized visual language of the 20th century.

Keith Haring died of AIDS related complications at the age of 31 on February 16, 1990.

Since his death, he has been the subject of several international retrospectives. The work of Keith Haring can be seen today in the exhibitions and collections of major museums around the world.

WOW! – Work of the Week – Ellsworth Kelly “Blue Green Black Red” 10/13/15

Ellsworth Kelly – Blue Green Black Red

Ellsworth Kelly

Blue Green Black Red

1971

Offset lithograph

29 3/4 x 27 1/4 in.

Edition of 100

Pencil signed & numbered

About This Work:

For more than fifty years, Ellsworth Kelly has worked to refine elements of the observed world into rigorous abstraction with a bold clarity and elegance. “My work has always been about vision, the process of seeing,” he notes. “Each work of art is a fragment of a larger context… . I’ve always been interested in things that I see that don’t make sense out of context, that lead you into something else.”

Maintaining a persistent focus on the dynamic relationships between shape, form and color, Kelly challenges viewers’ conceptions of space. He intends for viewers to experience his artwork with instinctive, physical responses to the work’s structure, color, and surrounding space, rather than with contextual or interpretive analysis.

His flat, immaculate compositions of pure line, simple forms, and saturated, unmodulated color are, in essence, found images, distillations of architectural details, shadows, plants, and other subtle forms that often might be overlooked. The contour of a leaf, the arch of a bridge and its reflection in water, and the soft curve of a hillside seen from the road have inspired paintings, sculptures, and prints alike. His art work represent a subjective interpretation of reality, rather than a descriptive copy of it.

Kelly’s arrangement of the complementary colors, which work to intensify one another at their intersections, is also an essential component of the work. In the 1971 lithograph Blue, Green, Black, and Red rectangles are laid, one on top of the other, in arrangements that suggest fragments of a remembered landscape. Perhaps it is several stories of a building, or perhaps a billboard looked, from a certain angle, or the way a shadow once fell.

Ordinary memories such as these, Kelly has said, prompt many of his works. ”As we move, looking at hundreds of different things, we see many different kinds of shapes. Roofs, walls, ceilings are all rectangles, but we don’t see them that way. In reality they’re very elusive forms. The way the view through the rungs of a chair changes when you move even the slightest bit – I want to capture some of that mystery in my work.”

About The Artist:

“I have worked to free shape from its ground, and then to work the shape so that it has a definite relationship to the space around it; so that it has a clarity and a measure within itself of its parts (angles, curves, edges and mass); and so that, with color and tonality, the shape finds its own space and always demands its freedom and separateness.” – Ellswoth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly is an American painter, sculptor, and printmaker associated with Hard-edge painting, Color Field painting and the Minimalist school. His works demonstrate unassuming techniques emphasizing the simplicity of form.

Although Kelly can now be considered an essential innovator and contributor to the American abstraction art movement, he was not always seen in such a positive light. It was hard for many to find the connection between Kelly’s art and the dominant stylistic trends For Example, observing how light fragmented on the surface of water, he painted Seine (1950), made of black and white rectangles arranged by chance.

He created a new freedom of painterly expression. He began working in extremely large formats and explored the concepts of seriality and monochrome paintings. As a painter he worked in an exclusively abstract mode. By the late 1950s his painting stressed shape and planar masses (often assuming non-rectilinear formats). His work of this period also provided a useful bridge from the vanguard American geometric abstraction of the 1930s and early 1940s to the Minimalism and reductive art of the mid-1960s and 1970s.

Kelly has distilled his palette and introduced forms never before. He starts with a rectangular canvas that he carefully paints with many coats of white paint; a shaped canvas, usually painted in a single bright color, is placed on top. The quality of line seen in his paintings and in the form of his shaped canvases is very subtle. The use of form and shadow, as well as the construction and deconstruction of the visible implies perfection.

For more information and price please contact the gallery at info@gsfineart.com

WOW! – Work of the Week – Clandestine Culture “I Came Back” 10/05/15

Clandestine Culture, I Came Back

Clandestine Culture

я вернулся, (I CAME BACK)

2014

Acrylic on Wood

81 x 48

Signed on verso

About This Work:

This work titled “I Came Back” or “я вернулся” (in Russian), by Miami Street Artist CLANDESTINE CULTURE,could not be more relevant today then ever before. “For those 25 years of age or younger, the Soviet Union symbol of the Hammer and Sickle, mean nothing. There is an age group that has never seen that symbol, or even knew of a Soviet Union” says the artist.

What this work represents is exactly what the artist wants that age group, 25 years or younger, to understand. That message is that history repeats itself. Painted in 2014, during Russia’s invasion into Crimea, and aggressive military intervention in Ukraine, this painting forewarns the world of what is to come. Russian President Putin flexes his political muscles, and lets the world know that he, and Russia are coming back. They are not the weakened Russia, that perhaps the world sees them as.

Fast forward to 2015, and we see President Putin is at it again, aligning himself with Syria, and positioning his stronghold in the Middle East. Showing that Russia is still a “super power”, and standing up to America

Painted in the old Soviet Union colors of red and gold, this painting is rather simple, but very powerful in its message. Depicting the iconic Hammer and Sickle, with star and olive branches as the main focal point, they symbol says it all. The words “I Came back” written in Russian lets us know, that this is a message about the present, and a warning about the future.

This is exactly what street art intends to do. Historically, street art has always contained a social, a political, and an environmental message. The art challenges the viewer to react not only to the artwork, but to the substantive issues, and surroundings that is being discussed.

Make no mistake, Street Art is not just pretty paintings on a wall. That would be simply called a mural. Street Art is much more important than that. Street Art has substance, context, and a concept. Whether it is Haring talking about AIDS, or Apartheid, Basquiat discussing issues of racism, drugs, and struggle of daily life, or Banksy’s witty paradoxical installations and wall drawings, Street Art has become a depiction and a reaction to the world most important issues, and struggles. Its “in your face” style, is arguably the most reactionary art movement that the art world has yet to witness.

Never before has an art movement, been so literal, and purposeful. Like his predecessors Haring and Basquiat, and his contemporaries Banksy and Shepard Fairey, CLANDESTINE CULTURE focuses on the world’s issues around us, and challenges us to acknowledge, question, and react.

About The Artist:

The artist chooses to remain anonymous. He hits the street with his face and head completely covered. He believes that the painting and the message is more important then the artist. He uses everyday people, images and words, to show that in the end, we are all part of one world wide culture…A CLANDESTINE CULTURE

For more information and price please contact the gallery at info@gsfineart.co

WOW! – Work of the Week – Roy Lichtenstein “Shipboard Girl” 9/28/15

Roy Lichtenstein, Shipboard Girl

Roy Lichtenstein

Shipboard Girl

1965

Offset lithograph

27 3/16 x 20 1/4 in.

Pencil signed

This work was not produced in a numbered edition.

About This Work:

Roy Lichtenstein, like many of his pop art contemporaries, was at first an abstract expressionist. Gradually, however, during the decade following his discharge from the army, he turned his attention increasingly to imagery drawn from such popular cultural sources as commercial advertising, romance and war comics, and cartooning in general.

Not only was Lichtenstein interested in the look of comic books, but also in the way they were produced. He carefully studied the way in which small dots of ink, known as Ben Day dots, were printed. He then enlarged these dots in his art to give his works the appearance of mechanically printed commercial products. Ben Day dots are the pattern of dots used in commercial printing to cheaply reproduce shading.

In the print Shipboard girl of 1965, we see Lichtenstein’s mature style in its rudimentary form. The image exemplifies all the qualities that his many paintings and prints of young women culled from romance comics exhibit — a girl, usually blonde, in extreme close-up, lips parted, her head tilted at an angle, with enormous, soft, liquid eyes, depicted at a moment of emotional climax.

Perhaps the woman in Shipboard girl is just enjoying the sun, or perhaps she is thinking of a shipboard romance that has soured. The life bouy lounging in the background is a visual pun suggesting that she is longing for a boy to rescue her from the as-yet-unreached turbulent seas of love. This sly humor is characteristically Lichtenstein.

What is salient about this work, however, is that here in its developmental stage, we have all the formal features which will come to characterize Lichtenstein’s subsequent output. Lichtenstein’s visual vocabulary, the characteristic elements of his style, are flat areas of unmodulated color, a schematized cartoon-like outline, the removal of anecdotal detail, and more importantly, the use of the Benday dots. Here we see him working towards a style which will become uniquely identifiable as his, and which ironically, over time and in its final formulation will replace the original in the very cartoon context from which it was derived.

About The Artist:

Roy Lichtenstein (October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was a prominent American pop artist. His work defined the basic premise of pop art better than any other through parody. Favoring the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produced hard-edged, precise compositions that documented while it parodied often in a tongue-in-cheek humorous manner.

In 1961, Lichtenstein began his first pop paintings using cartoon images and techniques derived from the appearance of commercial printing. This phase would continue to 1965, and included the use of advertising imagery suggesting consumerism and homemaking. His first work to feature the large-scale use of hard-edged figures and Ben-Day dots was Look Mickey in 1961. This piece came from a challenge from one of his sons, who pointed to a Mickey Mouse comic book and said; “I bet you can’t paint as good as that, eh, Dad?”

Lichtenstein had his first one-man show at the Castelli gallery in 1962; the entire collection was bought by influential collectors before the show even opened. It was at this time, that Lichtenstein began to find fame not just in America, but worldwide. His work featured thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent certain colors, as if created by photographic reproduction. However, rather than attempt to reproduce his subjects, his work tackled the way mass media portrays them.

In the 1970s and 1980s, his style began to loosen and he expanded on what he had done before. His style was replaced with more surreal works. His “mirror” paintings consist of sphere-shaped canvases with areas of color and dots. Lichtenstein also created a series of still lifes (paintings that show inanimate objects) in different styles during the 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s, Lichtenstein began to mix and match styles. Often his works relied on optical (relating to vision) tricks, drawing his viewers into a debate over the nature of “reality.”

Lichtenstein’s work is included in numerous museums, such as the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; Denver Art Museum, Denver; Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; Foundation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

For more information and price please contact the gallery at info@gsfineart.com

WOW! – Work of the Week 9/21/15

Robert Rauschenberg

Signs

1970

Screenprint

43 x 34 in.

Edition of 250 Pencil signed & numbered

About This Work:

Robert Rauschenberg’s “Signs” 1970, is one of the most sought after Rauschenberg screenprints because of the artwork’s incredible iconographic imagery and historical significance. Signs was originally commissioned by Time Magazine, with the intention that it would be used as the January edition cover for the year 1970. After considering the final composition, the executives at Time Magazine found the piece was more politically charged than they had hoped and decided against using it. It was felt that the composition, though stunning, was more of a recapitulation of the 1960’s than a welcome to the new decade.

After the dismissal by Time Magazine, Robert Rauschenberg’s trusted dealer Leo Castelli convinced him to print a limited edition screenprint of Signs. The edition was published by Leo Castelli in New York in an edition of 250; each signed, dated ‘70’, and numbered in pencil.

Signs is an astounding collage encompassing the monumental events and people of 1960’s America. Rauschenberg masterfully juxtaposes scenes of innovation like the moon landing with the destructive violence of the war in Vietnam and the civil rights movement. The revolutionary nature of the era is pronounced through the images of peace protestors at the top, whose rallies for change and peace are echoed by the voice of Janis Joplin deeply singing into her microphone. The iconic leaders of the era including JFK and his brother Bobbie Kennedy challenge the divisive violence of the wars and civil unrest, even as their forms and images transition into the faces of martyrs. The “Signs” of this transformative decade are woven seamlessly by Rauschenberg, and this screen print is known as one of his most important works of art.

About The Artist:

Robert Rauschenberg began what was to be an artistic revolution. Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for popular culture and his rejection of the angst and seriousness of the Abstract Expressionists led him to search for a new way of painting. He found his signature mode by embracing materials traditionally outside of the artist’s reach. He would cover a canvas with house paint, or ink the wheel of a car and run it over paper to create a drawing, while demonstrating rigor and concern for formal painting.

By 1958, at the time of his first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, his work had moved from abstract painting to drawings like “Erased De Kooning” (which was exactly as it sounds) to what he termed “combines.” These combines (meant to express both the finding and forming of combinations in three-dimensional collage) cemented his place in art history.

This pioneering altered the course of modern art. The idea of combining and of noticing combinations of objects and images has remained at the core of Rauschenberg’s work.

As Pop Art emerged in the ’60s, Rauschenberg turned away from three-dimensional combines and began to work in two dimensions, using magazine photographs of current events to create silk-screen prints. Rauschenberg transferred prints of familiar images, such as JFK or baseball games, to canvases and overlapped them with painted brushstrokes. They looked like abstractions from a distance, but up close the images related to each other, as if in conversation.

These collages were a way of bringing together the inventiveness of his combines with his love for painting. Using this new method he found he could make a commentary on contemporary society using the very images that helped to create that society.

In 1998 The Guggenheim Museum put on its largest exhibition ever with four hundred works by Rauschenberg, showcasing the breadth and beauty of his work, and its influence over the second half of the century.

For more information and price please contact the gallery at info@gsfineart.com