Tag Archives: ruscha

WOW! – Work of the Week – Ed Ruscha, Main Street

Ed Ruscha

Main Street

1990

Lithograph

8 1/2 x 10 1/4 in.

Edition of 250

Pencil signed, dated and numbered

About the work:

Ed Ruscha can be called the Jack Kerouac of art. Since his first road trip from Oklahoma City to Los Angeles in 1956, West coast Pop artist Ed Ruscha has been influenced by themes and icons surrounding America. The drive, which he took with his life long friend, classical guitarist and composer Mason Williams took about three days in a 1950 Ford sedan.

At the time, Ruscha, who has since become an avid photographer, did not own a camera and the only record of the trip is a log that the artist has kept over the years. The two friends, who were still teenagers at the time, used the log to keep track of their expenses as they were trying to stick to a budget. The log tells the story of their journey. Ruscha has said: “My art, really my life, evolved out of that trip. […] The log took the place of photographs. I got a camera soon after arriving in L.A.” American landscapes and text are what the artist is best known for, both of which emerged from from his cross country experience.

This week’s Work of the Week! WOW! is Main Street, by Ed Ruscha.

“Main Street” is part of the iconography of American life.

The “Main Street of America” branding was used to promote U.S. Route 66 in its heyday. Main Street is a generic phrase used to denote a primary retail street of a village, town or small city.

In small towns across the United States, Main Street is not only the major road running through town but the site of all street life, a place where townspeople hang out and watch the annual parades go by. In the general sense, the term “Main Street” refers to a place of traditional values. However, in the America of later decades, “Main Street” represents the interests of everyday people and small business owners, in contrast with “Wall Street”, symbolizing the interests of large national corporations.

Ruscha treats words as visual compositions which are typically categorized between pop and conceptual art. Works feature a word with strong connotations and a powerful visual impact. Ruscha uses the multiplicity of meaning to encourage the viewer to consider all the subconscious connotations of the word. This could be expanded to an exploration of the subconscious meanings hidden in all forms of language. The words elicits a mixed response within the viewer in which preconceived ideas about the subject are confronted and either validated or challenged.

Noting the transformation of Main Streets in American cities from small “mom and pop” businesses, ice cream parlours, and public square gatherings, to big box stores, chain restaurants, and consumers jay walking across the street, while burying their heads in their cell phones, the words Main Street takes on a much diff erent meaning than it once did. Ruscha’s Main Street, not only takes us back to the days of nostalgia, but also to modern times where Main Street meets and flirts with Wall Street. Innocence and American values are overshadowed by greed and technology. Overshadowed is the key word, because not only is Ruscha’s Main Street a sign of modernism replacing the past, but it also implies a sense of hope, that one day the traces of the past will lead to a happy memory, and a wanting to inject the future with the values of the days of old.

Rather than simply painting a word, Ruscha considered the particular font that might add an elevated emotion to the meaning much like the way a poet considers a phrase. By painting a word as a visual, he felt he was marking it as offi cial, glorifying it as an object rather than a mere piece of text.

The typography of the words in Main Street sets this piece apart from the majority of his work because it is not done in “Boy Scout Utility Modern.” Inspired by the Hollywood sign, the artist invented “Boy Scout Utility Modern” in 1980, and uses it regularly in his works. In this case, rather, the font seems closer in nature to “Times.” “Times” is a classic font, designed for its legibility so it is an obvious choice for a representation of the most famous street name in America: Main Street. Main Street is an ode and textual portrait of an American symbol.

Ed Ruscha is fascinated with the streetscape as a subject matter, and over the span of his six-decade career, Ed Ruscha has shaped the way we see it – depicting gas stations, signs or continuous photographs of Hollywood Boulevard. His works convey a distinct and bold brand of Americana. Ruscha explains. “I take things as I find them. A lot of these things come from the noise of everyday life.”

WOW! – Work of the Week – Ed Ruscha – Stranger

| Ed Ruscha Stranger 1983 Lithograph 30 X 22 1/2 in. Bon à Tirer (B.A.T.), from an Edition of 7 Pencil signed and annotated B.A.T. |

About the work:

“Huh? Wow!”

Language has often be inserted into visual art, yet no other artist uses it the way Ed Ruscha (roo-SHAY) does. His works are not pictures of words but words treated as visual compositions. “I like the idea of a word becoming a picture, almost leaving its body, then coming back and becoming a word again,” he once said.

Through his textual works, the artist has made his mark in a universe somewhere between Pop and Conceptual art. Over his six-decade-long career, critics have always had trouble classifying Ruscha because his oeuvre doesn’t fall into any predisposed category. As with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, his East Coast counterparts, Ed Ruscha’s artistic training in Los Angeles was rooted in commercial art. Ruscha’s style and subject matter, however, and the deadpan humor with which he executed them truly set him apart.

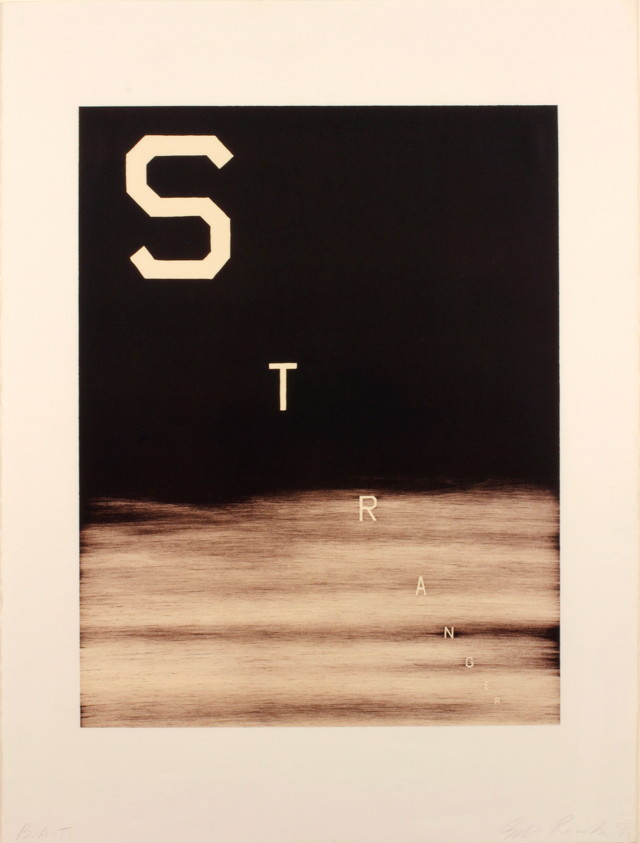

This week’s Work of the Week! WOW! is Ruscha’s Stranger, dating from 1983. It is a prime example of the techniques and style of the artist, and is part of a series of artworks of words over sunsets and night skies (which many refer to as landscapes) that Rsucha started producing in the early 80’s.

This particular example is the B.A.T. (bon à tirer, which translates as “good to pull”). The B.A.T. is the final trial proof, the one that the artist has approved, telling the printer that this is the way he wants the edition to look. Bon à tirer means ready for press.

The edition size of this work is extremely small of only 7 pieces produced. To have the B.A.T. is very rare.

Set against the backdrop of a dark night, the word “stranger” is depicted in an all-caps lettering of Ed Ruscha’s own invention named ”Boy Scout Utility Modern.” The font is a boldface print type with squared-off curves. Inspired by the truncated edges of the Hollywood sign, the typeface is transformed as letters take the place of characters on a stage, hovering in middle distance with a three-dimensionality all their own. The result? Images that land somewhere between clarity and mystery, symbol and signifier, art and poetry.

In using “stranger” as a visual, with a newly created typeface, the artist glorified it as an object rather than a mere piece of text, thus dignifying “stranger” as an object, bestowed with iconic status.

The influence of Hollywood and advertising are ever-present in the work of this LA artist and Stranger is no exception. This is highlighted in the way Ruscha placed his subject, covering the overall space of the plane. His bold “stranger” floats on a vast background, and mimics the opening screen of movies or fleeting glimpses of roadside billboards that must catch an audience’s attention in one compelling instant. The cinematic perspective of “Stranger” has a dramatic, raked perspective which can be traced to classic Hollywood black-and-white films. This unique diagonal positioning of the letters is disruptive and encourages the viewer to look at something ordinary in a different light.

The words Ruscha chooses for his creations have a multiplicity of meaning, which push the viewer to consider each connotation of the word. What is the first meaning that comes to mind when faced with the word “stranger?” It can be read as either noun or adjective. This ambiguity adds to the power of the work. Ruscha has always insisted that he never intends to instruct his audience, there is no hidden agenda, leaving each of us free to interpret the word.

Ruscha has said that “Art has to be something that makes you scratch your head,” but it doesn’t need to take itself too seriously either. His works are as playful as they are thought provoking. According to the artist, there is a simple rule for distinguishing between bad and good art. Bad art makes you say ‘Wow! Huh?’ Good art makes you say ‘Huh? Wow!’ It’s a good rule. ‘Huh? Wow!’ is most revealing when considered in terms of Ruscha’s own work. When observing his work in that context, the ‘Huh? Wow!” is what makes his art so enduringly great.

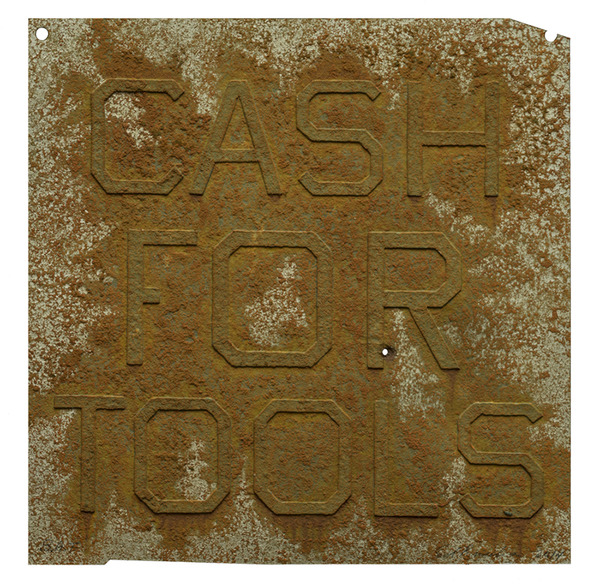

WOW – Work Of the Week – Ed Ruscha “Cash For Tools 2”

Opening Night at Art Aspen 2015

WOW! – Work of The Week

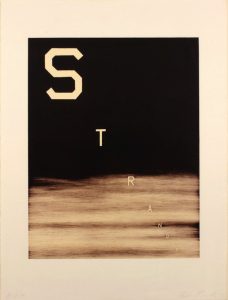

Ed Ruscha, Stranger

Ed Ruscha

Stranger

1983

Lithograph

30 x 22 1/2 in.

B.A.T.

This piece is pencil signed and numbered.

About This Work:

Since the early sixties, Ruscha has wittily explored language by channeling words and the act of communication to represent west coast American culture. Language, in particular the written word, has pervaded the visual arts, but no other artist has the command over words as Ruscha. His works are not to be understood as pictures of words, but instead words treated as visual constructs. His idea plays into the very essence of Pop Art.

Ruscha offers the capacity for multiple meanings of words, as seen in Stranger. Stranger can be a understood as a comparison of more or less than, or rather something or someone unknown. There is no definitive right answer, the meaning is based upon viewer discretion. The descending style in which he displays the word, both iconic and playful, elicits a similar ambiguity.

About Ed Ruscha:

Edward Ruscha has remained an important figure in American art since the early 1960s when his artwork first came to the fore as part of the West Coast Pop Art movement. Since that time, he has continued to develop his signature style, which combines words and images on the same visual field. By doing so, visual and verbal means of communication coexist and create a sense of friction. The words conjure mental images that do not necessarily describe what the eye actually sees in the painting.

A painter, printmaker, and filmmaker, Edward Ruscha was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1937, and lived some 15 years in Oklahoma City before moving permanently to Los Angeles where he studied at the Chouinard Art Institute from 1956 through 1960. By the early sixties he was well known for his paintings, collages, and printmaking, and for his association with the Ferus Gallery group, which also included artists Robert Irwin, Edward Moses, Ken Price, and Edward Kienholz. He later achieved recognition for his paintings incorporating words and phrases and for his many photographic books, all influenced by the deadpan irreverence of the Pop Art movement.

Ruscha has a talent for making the banal seem significant. He often reduces his subject to the minimum amount of detail needed for identification. Places and structures are often depicted as shadows. Ruscha is interested in language, and how that language can describe but not depict space. Words have been present in many of Ruscha’s paintings, often occupying the whole canvas. What they say is always clear. What they mean is more ambiguous

A major retrospective of Ruscha’s career opened at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. in June 2000 and traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, The Miami Art Museum, and the Modern Art Museum of Ft. Worth, TX. In 2001 Ruscha was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Letters as a member of the Department of Art.

Ruscha’s work has been exhibited internationally for three decades and is represented in major museum collections. Among his other public commissions are a mural commissioned for the Miami-Dade Public Library, Miami, Florida (1985 and 1989); and for the Great Hall of the Denver Central Library, Colorado (1994-95). Ruscha is represented in Los Angeles by Gagosian Gallery and in New York by Leo Castelli Gallery.

In 2004, The Whitney Museum of American Art exhibited an Ed Ruscha drawing retrospective, “Cotton Puffs, Q-tips®, Smoke and Mirrors: The Drawings of Ed Ruscha,”.

At the invitation of the U.S Department of State, four distinguished American museums recommended noted American artist Ed Ruscha to represent the United States at the 2005 Venice Biennale. The group consisted of the directors and curatorial representatives of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden of the Smithsonian Institution, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Mr. Ruscha nominated Linda Norden, the Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University, to serve as curator of his exhibition. The U.S. Department of State approved these recommendations.