Robert Rauschenberg

Signs

1970

Screenprint

43 x 34 in.

Edition of 250 Pencil signed & numbered

About This Work:

Robert Rauschenberg’s “Signs” 1970, is one of the most sought after Rauschenberg screenprints because of the artwork’s incredible iconographic imagery and historical significance. Signs was originally commissioned by Time Magazine, with the intention that it would be used as the January edition cover for the year 1970. After considering the final composition, the executives at Time Magazine found the piece was more politically charged than they had hoped and decided against using it. It was felt that the composition, though stunning, was more of a recapitulation of the 1960’s than a welcome to the new decade.

After the dismissal by Time Magazine, Robert Rauschenberg’s trusted dealer Leo Castelli convinced him to print a limited edition screenprint of Signs. The edition was published by Leo Castelli in New York in an edition of 250; each signed, dated ‘70’, and numbered in pencil.

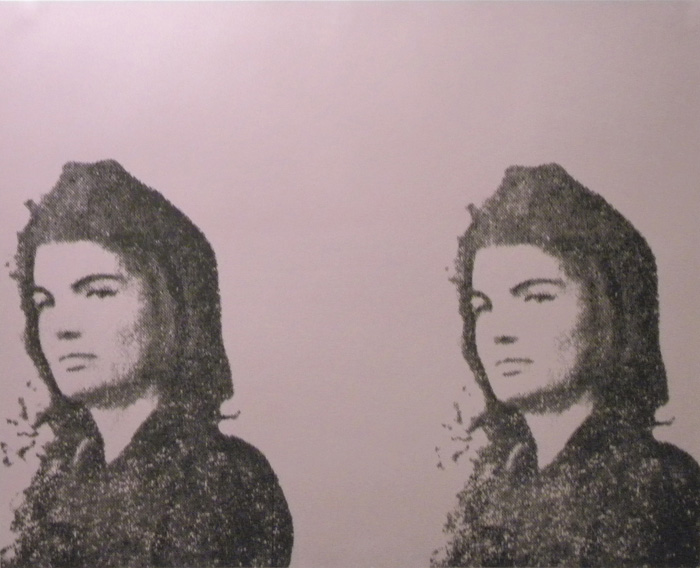

Signs is an astounding collage encompassing the monumental events and people of 1960’s America. Rauschenberg masterfully juxtaposes scenes of innovation like the moon landing with the destructive violence of the war in Vietnam and the civil rights movement. The revolutionary nature of the era is pronounced through the images of peace protestors at the top, whose rallies for change and peace are echoed by the voice of Janis Joplin deeply singing into her microphone. The iconic leaders of the era including JFK and his brother Bobbie Kennedy challenge the divisive violence of the wars and civil unrest, even as their forms and images transition into the faces of martyrs. The “Signs” of this transformative decade are woven seamlessly by Rauschenberg, and this screen print is known as one of his most important works of art.

About The Artist:

Robert Rauschenberg began what was to be an artistic revolution. Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for popular culture and his rejection of the angst and seriousness of the Abstract Expressionists led him to search for a new way of painting. He found his signature mode by embracing materials traditionally outside of the artist’s reach. He would cover a canvas with house paint, or ink the wheel of a car and run it over paper to create a drawing, while demonstrating rigor and concern for formal painting.

By 1958, at the time of his first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, his work had moved from abstract painting to drawings like “Erased De Kooning” (which was exactly as it sounds) to what he termed “combines.” These combines (meant to express both the finding and forming of combinations in three-dimensional collage) cemented his place in art history.

This pioneering altered the course of modern art. The idea of combining and of noticing combinations of objects and images has remained at the core of Rauschenberg’s work.

As Pop Art emerged in the ’60s, Rauschenberg turned away from three-dimensional combines and began to work in two dimensions, using magazine photographs of current events to create silk-screen prints. Rauschenberg transferred prints of familiar images, such as JFK or baseball games, to canvases and overlapped them with painted brushstrokes. They looked like abstractions from a distance, but up close the images related to each other, as if in conversation.

These collages were a way of bringing together the inventiveness of his combines with his love for painting. Using this new method he found he could make a commentary on contemporary society using the very images that helped to create that society.

In 1998 The Guggenheim Museum put on its largest exhibition ever with four hundred works by Rauschenberg, showcasing the breadth and beauty of his work, and its influence over the second half of the century.

For more information and price please contact the gallery at info@gsfineart.com