Tag Archives: indiana

WOW – Work Of the Week – Robert Indiana “KVF I”, from the Hartley Elegies

WOW – Work Of the Week – Robert Indiana “American Dream #5”

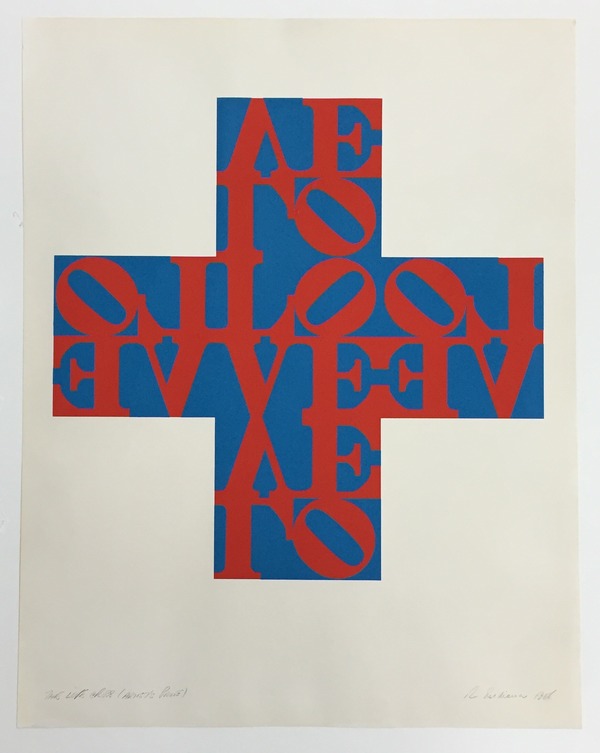

WOW – Work Of the Week – Indiana “Love Cross”

WOW! – Work of the Week 6/29/15

Robert Indiana, Zinnia, from Garden of Love

Robert Indiana

Zinnia, from Garden of Love

1982

Screenprint

26 5/8 x 26 5/8 in.

Edition of 100

This piece is signed, titled, dated and numbered in pencil.

About This Work:

Robert Indiana is most recognized for his very pop art LOVE works.

Zinnia is one of 6 works from Robert Indiana’s Garden of Love portfolio. Each of the six works is inspired and named after a flower.

About Robert Indiana:

“There have been many American SIGN painters, but there never were any American sign PAINTERS.” This sums up Robert Indiana’s position in the world of contemporary art. He has taken the everyday symbols of roadside America and made them into brilliantly colored geometric pop art. In his work he has been an ironic commentator on the American scene. Both his graphics and his paintings have made cultural statements on life and, during the rebellious 1960s, pointed political statements as well.

Born Robert Clark in New Castle, Indiana, in 1928, he adopted the name of his native state as a pseudonymous surname early in his career.

What Indiana calls “sculptural poems”, his work often consists of bold, simple, iconic images, especially numbers and short words like “EAT”, “HUG”, and “LOVE”.

Rather than using symbols from the mass media, Indiana makes images of words that focus on identity. Using them in bold block letters in vivid colors, he has enticed his viewers to look at the commonplace from a new perspective.

Despite his unique methods, several important aspects of Indiana’s works clearly identify him as a Pop artist. He manages to give a direct and honest description of American culture while appearing cool and uninvolved, much as Warhol did by simply reproducing images of superstars and soup can labels. In his most famous series Indiana took familiar words, usually three to five letters long, and repeated, reflected, or divided them. The simple familiarity of these words and the flattened manner in which Indiana presents them demonstrates the Pop art accessibility of content; viewers need not read much past the surface.

However, what distinguishes Indiana from his “Pop” colleagues is the depth of his personal engagement with his subject matter. Indiana’s works all speak to the vital forces that have shaped American culture in the late half of the 20th century: personal and national identity, political and social upheaval and stasis, the rise of consumer culture, and the pressures of history. He uses his art it to both celebrate and criticize the national way of life.

By presenting familiar words in new ways, he asks the viewer to reevaluate assumptions and emotions associated with those words. For example, no longer does the word “eat” simply describe an act, but a whole set of social conditions and practices associated with that act. Viewers might see the intimacy of eating and its central role in family, community, and romantic rituals or they might understand the negative aspects of eating in a society where high-fat, sugar-rich diets are the norm.

The same is true of Indiana’s most famous piece, his LOVE sculpture of 1966. By using block letters in bold, bright colors and dividing the word in half, he presents “love” in an unfamiliar way, thus asking the viewer what this familiar term means personally. His preoccupation with LOVE became an exploration of complicated relationships and his spiritual nature.