Tag Archives: calder

Gregg Shienbaum Fine Art will participate at Ink Miami Fair 2015

| Gregg Shienbaum Fine Art is proud to announce its participation at Ink Miami Art Fair 2015 | |||

| The show will be open December 2 to 6 | |||

| Come visit us at Booth 160 |

Click here for Miami Ink Art Fair press release

Pictures and news from the Fair will be coming soon!

Admission Hours:

Wednesday 11:00 am to 5:00 pm

Thursday 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Friday 10:00 am to 7:00 pm

Saturday 10:00 am to 7:00 pm

Sunday 10:00 am t 3:00 pm

For any information or to know what we will be showing at the Fair, please send us an email at info@gsfineart.com or call us at 305 456 5478

WOW! – Work of the Week

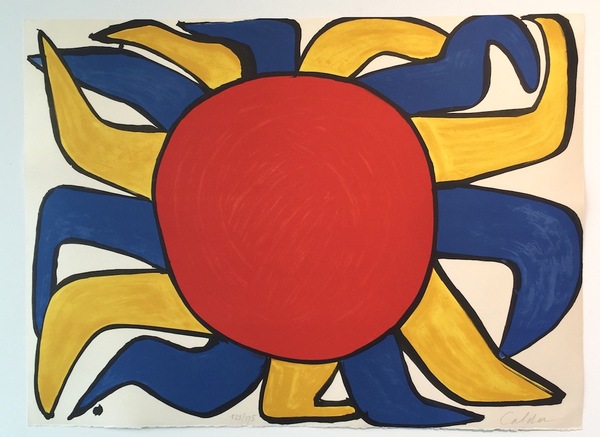

Alexander Calder, Pinwheel

Alexander Calder

Pinwheel

c. 1970

Lithograph

62 x 46 in.

Edition of 30

This piece is pencil signed and numbered.

About This Work:

Alexander Calder is best known for creating mobiles—sculptures composed of abstract shapes moving through spaces. Many of his lithographs can be seen as studies of movement for his mobiles, as well as the capturing of movement for his stabiles — stationary sculptures. Pinwheel is one of the larger prints Calder made to view and chronicle how the shapes would move on the mobile from an anterior view. With the primary colored shapes starting in one place and moving to an alternative axis only when the other shapes were in a particular place in space.

About Alexander Calder:

In a time of constant artistic upheaval, Alexander Calder’s aesthetic revolution concerned itself with a somewhat taboo topic in the art world — fun. His prolific and passionate output brought with it a humor and sense of play unlike any before. From a wire animal the size of a match box to a fountain filled with mercury to a seventy foot representation of a man in metal, Calder ignored the formal structures of art and in so doing redefined what art could be.

Born in 1898 in Philadelphia, Calder came from a family of artists. Both his father and grandfather were well-known sculptors, and his mother was a painter. Throughout his young life, Calder was more interested in mechanics and engineering than art. After graduating high school he attended the Stevens Institute of Technology, receiving his degree in 1919. Within a short while, however, his creative energies turned toward art and he enrolled in the Art Student’s League in New York. Working as a freelance illustrator, Calder began to paint and sculpt. Soon after his first one man show in New York, Calder left for Paris.

It was then that he began work on one of his most famous projects, the “Calder Circus”. The “Circus” was a miniature reproduction of an actual circus. Made from wire, cork, wood, cloth and other easily found materials, the “Circus” was a working display that Calder would show regularly. A mix between a diorama, a child’s toy, and a fair game, Calder’s “Circus” found many eager fans among the avant-garde. One of the methods used to create the “Circus” was the bending of wire to form realistic figures. Drawn to the ease and simplicity of it, Calder began to make wire portraits. A combination of a line drawing and of sculpture, these instant portraits represented a new possibility in three dimensional art.

By the early 1930s Calder had brought his “Circus” to the United States and back, and was living in Paris off the proceeds of his regular performances. While regularly fixing and adding to the “Circus”, Calder began to show and work on wire and wood sculpture as well as painting. It was around this time that he became interested in the work of the Surrealist painter Joan Miró and the modernist painter Piet Mondrian. Both men had gone beyond abstraction and were making paintings of colors and shapes with no direct reference to the outside world. Enthusiastic about this embrace of form and color, Calder began to make moving sculptures in a similar vane.

Beginning with painted aluminum and wire, Calder created motored objects that could move to create different visual effects. In a short while, however, he realized that the mechanized movement didn’t have the fluidity or the surprise he wanted in his work. He decided to let them hang and have the wind or a slight touch begin their movement. When the experimental French artist Marcel Duchamp saw them, he named them “mobiles” (a pun on the French for “to move” and “motive”). These new sculptures, arranged by the chance operations of the wind, went against everything that sculpture had been. They were not monumental, nor were they sober. They were simply about form and color and the joy in creating both. So, in his early thirties Alexander Calder had not only found a project he would continue for the rest of his life, he had created a unique form of art, the mobile.

In 1933, Calder and his wife, Louisa James, moved to Roxbury, Connecticut, where they would spend the rest of their lives. Working on hundreds of small mobiles, Calder became interested in making large, more substantial works as well. Using similar colorful abstract forms, he made giant metal structures whose shapes and colors stood out bravely in both rural and urban settings. Known as “stabiles,” these works often had a similar whimsical quality to the smaller kinetic pieces. By the time of his first major show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943, Calder’s quiet revolution was known internationally. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s he was commissioned to create site specific “stabiles” and had major retrospectives in a number of cities including Amsterdam, Berne, and Rio de Janiero.

By 1970, Calder had reached the height of his fame. He had worked regularly creating thousands upon thousands of objects—everything from jewelry to children’s toys to major monuments for the Lincoln Center in New York and UNESCO in Paris. That same year his gifts were honored again with a comprehensive show at the Guggenheim Museum and a smaller one at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1976, Alexander Calder died. Throughout his life, his commitment to creating work free from the pretensions of the art world and accessible to all, never stopped him from making exquisitely beautiful and important sculpture. In a century that saw the forms of art and literature reinvented regularly, Alexander Calder stands out as one of the great pioneers of his time. Adapted from PBS.